My voice has left me. There’s paralysis in the muscles and nerves of my left vocal cord. For now all I can manage is a hoarse whisper and depending on what doctor I consult I’m not even supposed to do that. I’m on a heavy régime of Nimodipine; a class of medication called calcium channel blockers usually used to reduce brain damage caused by the excessive bleeding from an aneurysm. Yet its unintentional side affect is rejuvenating damaged nerves. I’m on a dose three times what’s considered normal and I have to constantly monitor my blood pressure.

“If it drops below 100/60,” said my doctor. “Get yourself to the ER.”

The drug’s other “adverse affects” range from constant dull headaches, and abdominal “discomfort.” But the worst part is the fatigue. I’m tired all the time. By 3pm I’m wiped out. I nap a lot. My brain glazes over. I feel lethargic. I feel despair. I crawl in bed; pull up the duvet, and snuggle with my depression like we’re having an affair.

“Do you need help?” The drugstore clerk is young and energetic and exhibiting a novice’s desire to be accommodating. Or maybe it’s forced as part of this establishment’s directive requiring its employees to be customer centric.

“No thanks,” I hiss behind my double masks.

The pixie-faced clerk’s eyes go wide; she takes a step back, and glances around either looking for help or an escape route. “Um… Covid testing is over by the pharmacy.”

I give her the thumbs up. I’m not looking for a Covid test. I’m just going about my business buying a “family size” bag of original flavor Ricola for my sore throat. But I throw in a couple of raspy coughs for theatrical effect just to send her scurrying away.

It’s intense and disturbing to be on the receiving end of people’s reactions when you can’t talk. There’s an assumption that something is gravely wrong, and believe me, not being able to talk is wrong, gravely or otherwise. But there’s more to it then that. My inability to verbally communicate touches an area where people get really uncomfortable. They are either repulsed, annoyed, confused, or afraid. I have yet to run into a stranger that showed concern or even the slightest amount of compassion. And this includes a number of people in the medical field.

An employee at FedEx shouted, as if I was deaf, “Sir, you’ll have to speak up!” When I stepped closer to the counter he backed even farther away.

A nurse talking my blood pressure kept asking me questions regarding my current medications, and when she couldn’t hear my responses immediately became agitated, walked across the office, and complained rather loudly to another nurse, “Why do they come in when they’re unable to comply to the smallest requirements? I swear I get the weirdest patients. The next guy will probably be in a coma.”

A doctor during a telehealth appointment, “Are you trying to talk like that? What happens when you just talk normally?”

According to some outdated and obscure research two thirds of the world’s population related feeling “uncomfortable when talking to a disabled person.” A majority of them stated, “I don’t know how they want me to act around them,” or, “I don’t want to offend them, so I ignore them.”

Apparently people don’t do well when other people make them uncomfortable. It’s like they’re forced to reckon with the part of themselves that isn’t perfect. Or that they too are vulnerable and at a moment’s notice could be in the same predicament. Technically it’s called “Ableism” – which is the discrimination and social prejudice against people with disabilities and/or people who are perceived to be disabled. Essentially what it comes down to is disabled people are perceived as broken, defective, weak, and worst of all, possibly contagious.

I can’t imagine having to deal with shit like that all the time. But maybe I better get used to it? Although to be honest… I’m really sorry that I make you feel uncomfortable, but how about you go fuck yourself?

There are some medical procedures where you realize just how rudimentarily inept and barbaric modern western medicine truly is.

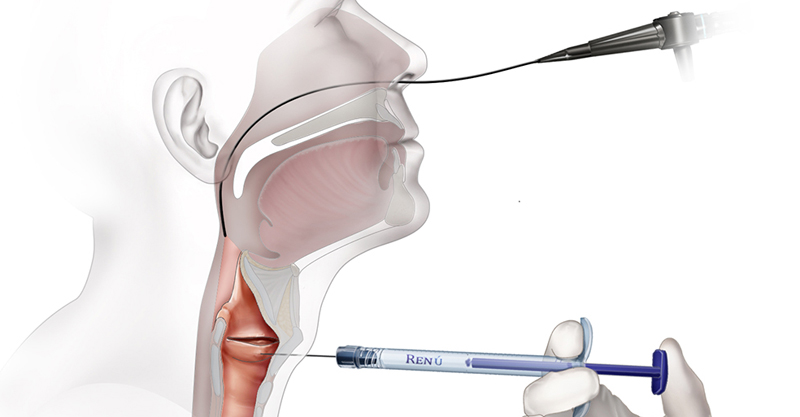

Yesterday I saw the doctor for an “in office” procedure that consisted of injecting juvaderm (a cosmetic “filler” normally used to “restore facial contours” e.g. puff up that old skin to get rid of wrinkles), into my throat. In order to make my paralyzed vocal cord thicker and move its inner edge closer to the middle so that it doesn’t have to do all the work on its own.

I don’t know what or how I thought this “procedure” was going to be done. But I wasn’t ready for the seemingly horrific idea that the surgeon was going to shove a long needle through the front of my neck and into the other side of my throat. While watching it all on a tv screen seen through an endoscope—a thin, flexible tube with a tiny camera and a light—that was shoved down my nose. Of course there was a lot of local anesthesia, and the inhaling of lidocaine mist that produced an overly familiar cocaine-esque numbing drip at the back of my throat. The doctor then had me lean forward, chin up, and I still felt a sharp poke, and then a hard pressure of an injected material somewhere inside of my neck.

Letting someone do this went against all my survival instincts. But I closed my eyes and concentrated on my breath. The problem is the injections didn’t work the first time. Or the second. Or the fifth. Or the seventh. Fifteen minutes of this and trails of blood were running down my neck onto the white towel draped across my chest. I started to feel cold and distant. My limbs began involuntarily shaking.

“Try talking.” I opened my eyes and the doctor and nurse are staring at me over their masks. A guttural hiss emanated from my throat. I swallow and feel pain.

“You might feel a bit sore. I took a biopsy just in case.”

Great, now I’ve got cancer.

“Well, I’m sorry to say this isn’t working.” But the doctor doesn’t sound apologetic, more like he’s frustrated and irritated. “I’ll have to schedule your for surgery. But due to covid overtaxing the health system most ‘non-essential’ surgery has been put on hold. We’ll have to get back to you when we can.”

I asked the doctor why this has happened, why I can’t talk, why my vocal cord had suddenly become paralyzed. He said he doesn’t know. Thinks it may be viral. Only he can’t say for sure. But he warned it might be a very long recovery and there are other options if surgery doesn’t work. I immediately thought of an electrolarynx, you know, one of those robotic voice boxes that we’ve all seen in movies and tv shows. But he shook his head and mumbled something about fat implants, reconstructive procedures, and I’ll probably be seeing a speech therapist.

“It could take a year,” he said.

It’s been 70 days since I was able to talk.