My father died last Sunday morning. I was awakened by the call around 3 am. His partner Maya told me he’d passed away and I couldn’t find the words to respond. He’d been sick for the last two years. Cancer and chemo and his body hadn’t reacted well to both. Final diagnosis was Leukemia—a direct result of the chemo’s radiation “therapy” destroying his immune system. My father had been despondent, tired, and detached. He felt the medical world had failed him and didn’t want to spend his last days in a hospital just to die amongst the uncaring surroundings of beeping heart monitors and endless blood draws.

Six weeks ago, another Sunday, my father called to tell me he had Leukemia and he’d made the decision not to seek treatment. I had just finished buying vegetables at the Hollywood Farmer’s Market, my usual Sunday morning thing to do. I was sitting in my car. Numb with fear and regret. My father’s voice faint and calm. “I have to come out and see you,” I finally blurted out.

My father lived in Somerville, Massachusetts. Just over the border from Cambridge, a few blocks from where we lived when we first moved to Boston. When I was nine years old he’d completed his Fulbright and been appointed professor of linguistics and education at Harvard University. It was 1965. Vietnam was in full swing. He protested the war, refused to pay his taxes, and the FBI froze his bank account. By 1968 he found his home, professor of linguistics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Ultimately becoming chairman of the linguistics program, and then head of the department for linguistics and philosophy. He was well liked, loved and admired. Noam Chomsky was his friend and colleague.

A month ago I flew out to see him. He was very sick and even though we didn’t get a chance to talk much, I still was able to tell him I loved him. He said, “I had a picture in my mind that I’d just come home, lay on the couch, people would come by, and then I’d quietly die. But that isn’t happening.” I flew back dreading the inevitable outcome.

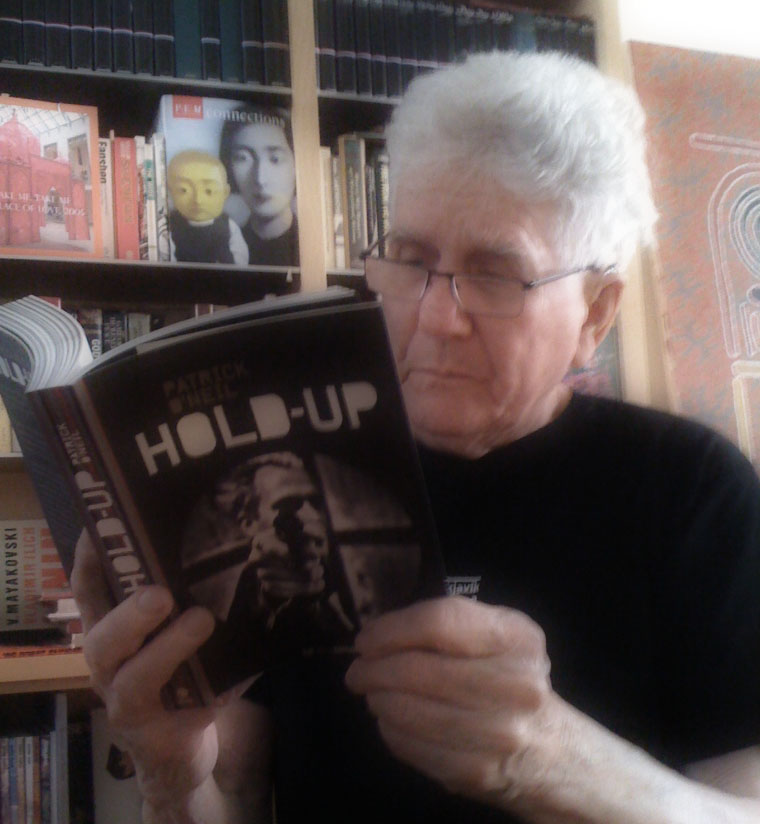

In the darkness I fumbled for the words that weren’t coming. I held the phone against my ear well after Maya had hung up. Earlier in the evening I’d had a feeling. I’d known my father was going to die that night. Yet I still wasn’t prepared. My first selfish thought was what a fucked up horrible son I’d been. I felt the shame of my father having to come to terms with his son the junkie bank-robber. Self-forgiveness is hard. In fact it’s impossible. I cried tears. I said I was sorry. I spoke out loud to the spirit of a man that didn’t believe in the afterlife. My heart ached. I can only hope that everything I have done in the last twenty years has made up for every fucked up thing I did in the previous thirty. I’d like to think he was proud of me. The picture used in a few of his obituaries was of him reading the French version on my memoir, so I’ll take that as a sign that he was. I know I was proud of him. I hate that I’ll never see him again.

There is never enough time in this life.

Hold those you love close.